By C. Tyler Morrison, MEd, MA, CSCS, RSCC*D

As strength coaches or sport coaches in charge of the weight room, one of our core responsibilities is helping athletes get stronger through progressive overload and foundational movement patterns. The story of progressive overload dates back to Milo of Croton, who became stronger by lifting a growing calf daily until it became a full-sized bull. While the principle is simple, strength gains in real life are far from linear.

To create adaptation, we must understand how to manipulate training variables. We have access to many tools—sandbags, kettlebells, medicine balls, dumbbells, machines—but few are as versatile and widely used as the barbell. Barbells are a staple in nearly every strength facility, yet not all barbells are created equal, and the emergence of specialty bars has added new dimensions to programming.

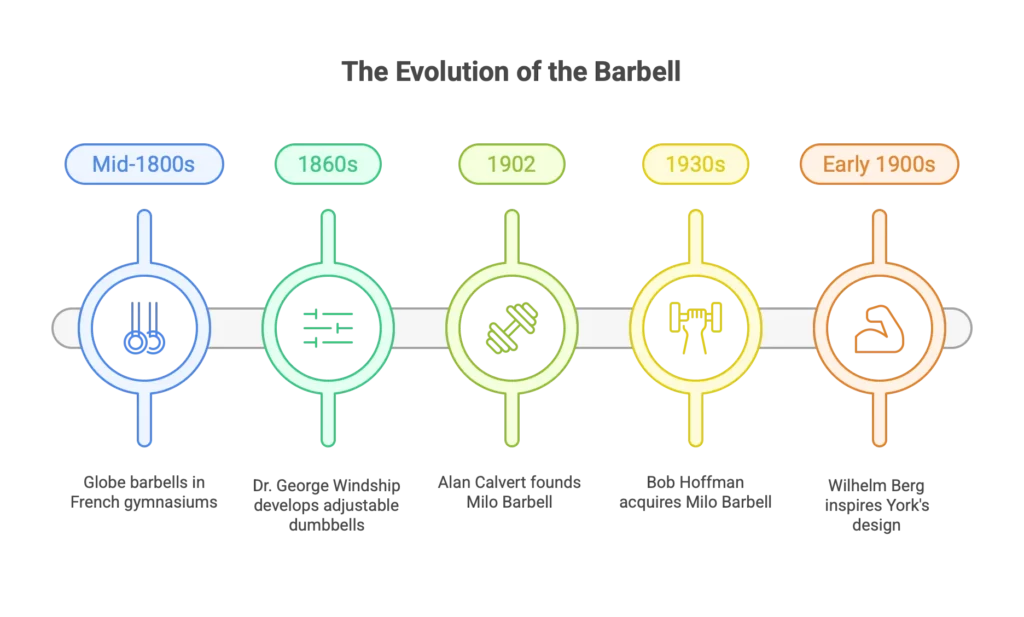

The Evolution of the Barbell

- Mid-1800s: Globe barbells seen in French gymnasiums operated by Hippolyte Triat. Globes could be filled with shot pellets to adjust the weight.

- 1860s: Dr. George Windship develops adjustable dumbbells, precursors to modern barbell plates.

- 1902: Alan Calvert founds Milo Barbell in Philadelphia, influenced by strongman Eugene Sandow.

- 1930s: Bob Hoffman of York Barbell acquires Milo Barbell, evolving it into a more standardized tool for training.

- Early 1900s: Wilhelm Berg’s German-made Olympic-style bar inspires York’s design. Berg is considered the “father of the German sports industry.”

Not All Barbells Are Equal

It’s important not to prescribe one type of bar for all athletes. Mobility, injury history, training experience, and individual needs should all be considered. Some athletes may benefit from specialty bars, while others can use traditional Olympic bars. And while loading the bar seems intuitive, athletes must understand the importance of respecting the bar’s starting weight—especially younger lifters.

Common Barbell Types and Their Uses

- Olympic Barbell: 45 lbs, 2” sleeves, versatile for most lifts.

- Training Bars: Lighter (5–35 lbs), great for beginners or youth.

- Trap/Hex Bar: Reduces lumbar stress; ideal for deadlifts.

- Safety Squat Bar: Changes bar position to reduce shoulder strain.

- Cambered Bar: Shifts center of gravity for varied loading stimulus.

- Swiss/Multi-Grip Bar: Allows neutral grip; ideal for athletes with wrist or shoulder issues.

- EZ Curl Bar: Changes joint angles; useful for curls or pressing.

- Axle Bar: Thicker grip and no spin, great for landmine and grip-intensive lifts.

- Deadlift/Power Bars: Higher load capacity, aggressive knurling.

- Oscillating Bars (Tsunami, Bamboo, Earthquake): Generate instability to improve neuromuscular control.

- Log Bar: Used in strongman competitions, excellent for varied pressing challenges.

Curious what these bars look like? A quick Google image search of any barbell listed above—like “Safety Squat Bar” or “Tsunami Bar”—will give you a clear visual example. Seeing the design and unique features of each bar can help you better understand how and when to use them in your program.

Barbell Training and Movement Patterns

Barbells and specialty bars can be integrated into all key movement patterns:

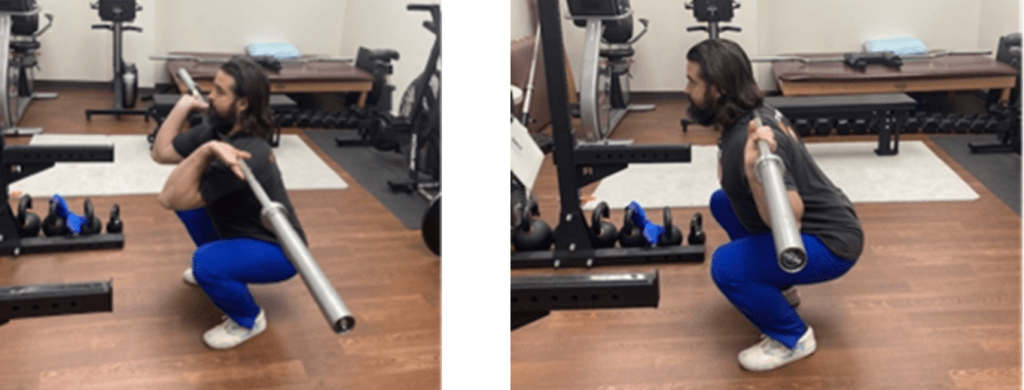

- Squat: Use Olympic, safety squat, or cambered bars. Box squats offer regression or variation.

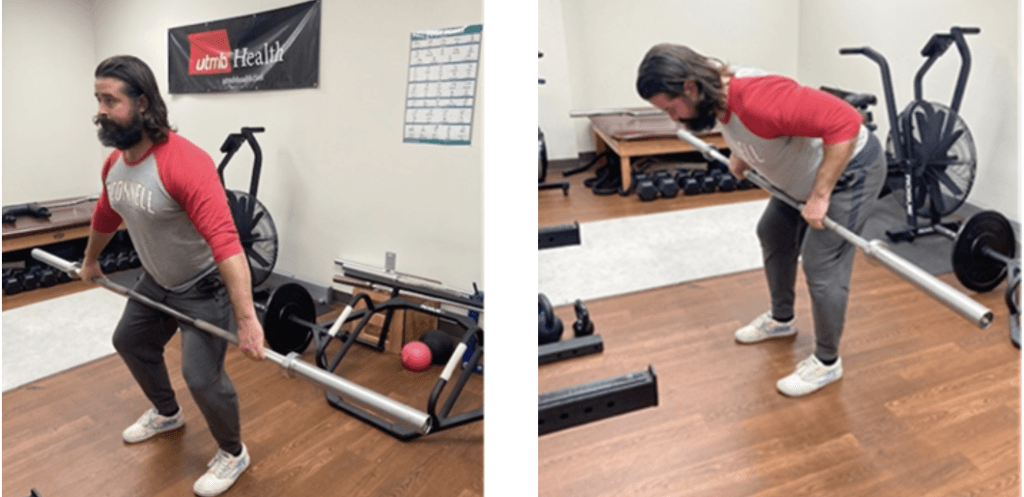

- Hinge: Choose between trap bar, sumo deadlift, or traditional deadlift patterns.

- Lunge: Can be performed with front or back rack bar positions.

- Push/Pull: Incorporate vertical and horizontal movements; adjust grip using specialty bars.

- Carry: Trap bar or barbell suitcase carries develop core and grip strength.

- Core & Conditioning: Loaded movements inherently challenge the core; manipulate rest for conditioning benefits.

Clarifying Terminology

It’s crucial to use consistent language when coaching. Not all barbell use is “weightlifting” (a term reserved for Olympic lifting: the snatch and clean & jerk). Coaches should differentiate between powerlifting (bench, squat, deadlift), Olympic lifting, and general resistance training.

Understanding these differences enhances clarity and ensures athletes develop proper technique for the right goal.

Training Variables Coaches Can Manipulate

- Tempo: Eccentric, isometric, concentric control

- Rest: Adjusted based on effort and goals

- Exercise Selection: Compound vs. single joint

- Exercise Order: Complex to simple or skill-based

- Volume: Sets x reps or total duration

- Frequency: Weekly session count

- Intensity: Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), Reps in Reserve (RIR),Ppercentage of your maximum lift for a single repetition (%1RM).

- Range of Motion: Full or partial

Sample Weekly Training Plan: Barbell-Based Strength & Power

Training Goal: Improve total-body strength, power output, and movement quality

Target Group: Intermediate high school athletes (multi-sport or general population)

Duration: 4 sessions/week

Training Phase: Early off-season (8-week block)

Key Training Variable Strategy

| Variable | Applied Strategy |

|---|---|

| Tempo | Controlled eccentric (3s), brief isometric (1s pause), explosive concentric (X) |

| Rest | 90–120s for strength work; 30–45s for accessory lifts |

| Exercise Selection | Emphasis on compound lifts; isolation work used for balance and volume |

| Exercise Order | Power → Main Lift → Accessory → Core/Conditioning |

| Volume | 3–5 sets x 3–8 reps based on the movement’s complexity and goal |

| Frequency | 4 sessions/week (Upper/Lower split) |

| Intensity | 70–85% 1RM for strength; RPE 7–9; RIR 1–3 |

| Range of Motion | Full ROM prioritized; partial ROM for overload or mobility limitations |

Weekly Layout

| Day | Focus |

|---|---|

| Monday | Lower Body Strength & Power |

| Tuesday | Upper Body Push & Pull |

| Thursday | Lower Body Speed & Volume |

| Friday | Upper Body Power & Accessory |

Day 1: Lower Body Strength & Power

| Exercise | Sets x Reps | Tempo | Rest | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hang Power Clean | 4 x 3 | X/0/X | 90s | Focus on speed and bar path |

| Back Squat | 5 x 5 | 3/1/X | 120s | 75–80% 1RM; cue bracing and depth |

| Barbell RDL | 3 x 8 | 3/0/1 | 60s | Emphasize hamstring control |

| Walking Lunges (Dumbbell or Barbell) | 3 x 8/leg | 2/0/2 | 60s | Use safety bar or goblet if needed |

| Hanging Knee Raise | 3 x 12 | Control | 30s | Core focus with tempo awareness |

To view the portion of the article, you must be an NHSSCA Professional or Student Member. Sign In to access, or CLICK HERE to become a Professional Member today.

The Force-Velocity Curve: Training Fast vs. Heavy

Training adaptations depend on where movements fall on the force-velocity curve. Olympic lifts focus on velocity, while powerlifting emphasizes force. VBT (velocity-based training) tools can help measure and optimize this, but intent matters just as much. Even without technology, coaches can cue athletes to “move with speed” or “control the descent.”

Understanding bar speed helps tailor training to the season and sport-specific needs of each athlete.

Force-Velocity Curve Integration – 4-Day Sample Weekly Training Plan

The Sample Weekly Training Plan intentionally integrates movements across the force-velocity curve to develop both strength (force) and power (velocity):

- High-Velocity Movements (e.g., Push Press, Trap Bar Jump Shrug, Med Ball Throws, Push Jerk) are programmed early in sessions when the athlete is freshest, allowing maximal intent and neuromuscular efficiency.

- High-Force Movements (e.g., Back Squat, Bench Press, RDL) emphasize controlled eccentrics and high-intensity loading to develop maximal strength and structural integrity.

- Tempo prescriptions (e.g., 3/1/X) are used to reinforce time under tension, enhance motor control, and guide athletes toward a better understanding of bar speed.

- While VBT (velocity-based training) tools can enhance precision, intent is king. Cue athletes to “explode” through the concentric phase on power movements and “own the descent” during eccentric phases—even when not measured digitally.

- Coaches should adjust the emphasis on fast vs. heavy lifts depending on the seasonal needs:

- Off-season: Emphasize force (strength building)

- Pre-season: Blend force and velocity (transmutation phase)

- In-season: Prioritize velocity (power and maintenance)

By intentionally applying movements across the curve, this plan ensures athletes develop force production across a broad spectrum, improving sport performance and resilience.

The 4-Day Strength and Conditioning Program featured in this article was developed using integration principles informed by the High School Strength Coach Certified (HSSCC) framework. It demonstrates how to apply barbell fundamentals with intent—leveraging tempo, exercise order, load, and movement variation to meet athletes where they are and guide them forward. Coaches who earn the HSSCC certification gain access to frameworks like this, empowering them to program with precision, reinforce sound technique, and build durable, high-performing athletes.

Final Thoughts: Respect the Tool

The barbell is a time-tested, adaptable training tool. Whether you use Olympic lifts or variations with specialty bars, the principle remains: select the right tool for the right athlete at the right time. Respect the law of accommodation—everything works, until it doesn’t. Rotate tools, adjust variables, and focus on stimulus to drive adaptation.

Barbells, like any tool, are only effective when applied with intention and understanding. Practice the movements yourself. Refine your coaching cues. And never stop learning.

About The Author

Coach Tyler Morrison has an official title as an Exercise Physiologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch, but he is a strength coach by trade. He works in the Rehabilitation Department where he performs outreach to local school systems in a Sports Medicine & Performance capacity. Coach Morrison has been in the field for over a decade and is currently pursuing his PhD in Physical Culture and Sport Studies from the University of Texas.